Working memory.

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to understand how working memory operates in relation to the perceptual and cognitive processes. The paper then discusses the limited capacity, short duration, and highly volatile nature of working memory and its implications on the design of ICICIDirect’s online investment management platform. Further, the paper analyzes the workload imposed by the investment process in comparison to the working memory capacity. The paper also discusses emotional factors like anxiety and motivation that affect working memory capacity. The paper also focuses on other factors like age, learning disorder and attentional disorder that can influence the working memory capacity.

1. Working memory

(Baddeley, & Hitch, 1974) defines working memory as a limited capacity workspace that stores information temporarily and manipulates the information for complex cognitive tasks such as language comprehension, learning, and reasoning. To explain the simultaneous storage and processing of information in working memory, Baddeley proposed a model according to which the working memory was divided into three sub-components: an attentional-controlling system called central executive, a visual image manipulation component referred to as the visuospatial sketchpad, and a speech based information storage and rehearsal system known as the phonological loop. The central executive is also responsible to coordinate information from the visuospatial sketchpad and the phonological loop (Baddeley, & Hitch, 1974). In 2000, Baddeley extended his working memory model by adding a fourth component, the episodic buffer. The episodic buffer integrated visual, spatial and verbal information from various domains in a chronological order. It is controlled by the central executive and exchanges information in both the directions with long-term memory (Baddeley, 2000). We can thus say that working memory is coded phonologically, visually, and semantically providing multiple priming points to access the long-term memory.

1.2. Working memory – limited capacity

(Miller, 1956) In 1956, Miller brought to attention the limitations in the working memory capacity, then referred to as immediate memory, to process information. To understand Miller’s conclusions, it is essential to understand the definition of

two terms:

1) Span of absolute judgment: It is the limit with which the immediate memory can accurately distinguish between magnitudes of unidimensional stimulus. Miller determined that this limit is somewhere close to seven. Absolute judgment

is thus limited by the amount of information.

2) Span of immediate memory: It refers to the number of items, or chunks, that can be retained in immediate memory. Coincidentally, this number too is somewhere close to seven.

Miller derived

that the span of immediate memory is independent of the amount of information present within each item. This implies that the memory span can be significantly increased by grouping the input information into familiar chunks (Miller, 1956). For example,

chunking of characters or words into strings that can be interpreted meaningfully. However, the total number of strings that can be retained by the memory is constant and roughly equal to seven.

(Baddeley, & Hitch, 1974) conducted experiments focusing on three tasks: verbal reasoning, language comprehension, and free recall of unrelated works. The experiments demonstrated that in case of increased memory load i.e. 6 items, degradation in the performance of the three tasks was observed. In this research, Baddeley and Hitch also pointed out the phonological similar effect which states that recall of similar sounding words is poorer than dissimilar sounding words.

(Luck, & Vogel, 1997) Luck and Vogel elaborated on the concept to chunking in visual working memory and indicated that the visual working memory is able to retain information of about roughly four unidimensional stimuli at once. This research also indicated that the visual working memory can retain information of at least four objects defined by a conjunction of four features (Luck, & Vogel, 1997). This implies that the visual working memory stores a limited number of integrated percepts of objects whose features are combined by the attentional resources.

The above research provides evidence to support that working memory has a limited capacity which depends on the categories and features of the chunk. For example, one can hold more short words in working memory than long words (Baddeley et al., 1975). Working memory functioning at full capacity or beyond can lead to degradation of task performance. Chunking thus helps reduce the number of items in the working memory. Effects of chunking can be significantly improved by binding information cognitively using the meaningful models or representations from the long-term memory. It can be used as a resource for rehearsal and learning, making sure that information is retained in the working memory.

1.2. Working memory – limited duration and highly volatile

(Peterson, & Peterson, 1959) conducted experiments to demonstrate that information is retained in short-term memory for about 15 seconds after which it decays. (Baddeley, 2000) suggested that the auditory memory traces decay after few seconds in the phonological store of the working memory unless it is restored through rehearsals. (Baddeley et al., 1975) suggested that working memory can retain as many words that can be spoken within two seconds. This was termed as the word-length effect. (Zhang, & luck, 2009) demonstrated through experiments that visual working memory can hold color and shape information for up to four seconds with negligible loss in quality and quantity. (Goldstein, 2010) According to Goldstein, information in working memory is held for about 10-15 seconds unless it is actively rehearsed or attended to.

It is observed that the last item in a list is retained in a more privileged or attended state (Hu et al., 2016). This is referred to as the recency effect and is concluded to be volatile and vulnerable to various attentional manipulations (Hu et al., 2014). (Lustig et al., 2001) performed series of experiments to understand the effects of interference on the working memory span. The experiments’ results provided evidence that proactive interference hinders comprehension of new information. In other words, while in the process of memorizing a list, it gets difficult to remember the latter part of the list since the earlier memorized part of the list starts interfering. There are two types of errors that can occur in a serial recall – transposition and intrusion errors. Transposition error occurs when an item, from a presented set, is recalled in the wrong position. Intrusion error occurs when an item not included in the presented set is recalled (Henson, 1998).

Form these studies we can see that working memory has limited and short duration. However, there are no exact conclusions quantifying this limitation. We can hence imply that the duration of working memory is restricted to few seconds unless the retained information is actively rehearsed. Also, the information stored in working memory is vulnerable to attentional manipulations and errors. This proves that working memory is highly volatile and that this nature of working memory can, in turn, affect its duration and capacity too.

1.3. Role of emotion in working memory

(Taylor, & Spence, 1952) Anxiety can result in errors in task performance. Taylor and Spence conducted experiments with two group of subjects and found that the anxious subjects are prone to making significantly more errors than the less anxious subjects. Also, a larger number of trials were required by anxious subjects to learn the task. (Shackman et al., 2006) One of the experiments conducted by Shackman et al. revealed that individuals with high levels of self-consciousness projected more intense anxiety and relatively worse spatial working memory performance in the absence of threat. (Eysenck et al., 2007) Multiple experiments performed by Eysenck et al. provided satisfying results indicating that anxiety results in degradation of working memory performance. The experiments concluded that anxiety affects efficiency more than effectiveness and the negative effects of anxiety are directly proportional to the number of tasks in the central executive. Anxiety hinders the shifting function that leads to focusing on distractions posing threats. The experiments further concluded that anxiety reduces the ability to perform tasks under stressful conditions (Eysenck et al., 2007). It is hence very imperative to reduce anxiety caused by the design in order to improve task performance. This can be done by using familiar terminologies and images, controlling the information density, reducing unnecessary redundancy and clutter, and by limiting information to one task.

(Brose et al.,2012) Experiments conducted with young individuals concluded that lack of task-related motivation had negative effects on working memory capacity. (Krawczyk, & D'esposito, 2013) proved that working memory was influenced by motivation in the form of monetary loss too. (Avery et al., 2013) On the other hand, motivation also plays a significant role in improving working memory performance which in turn plays an important role in the goal achievement process. Motivation thus can be seen as the great enabler that can help users extend their cognitive capabilities to overcome limitations that otherwise would have affected their performance in a negative way.

However, it is important to note that low or high levels of anxiety or motivation, which are nothing but forms of arousal, will lead to a decline in task performance. But a certain moderate level of anxiety and motivation can result in optimum performance outcome. (Staal, 2004).

1.4. Other factors influencing working memory capacity

In the above section, we saw how emotions, especially motivation and anxiety affect the working memory. Similarly, other factors influencing working memory capacity are age, learning disorders, and attentional disorders. (Swanson, 1999) determined that readers with learning disorder operate at a lower working memory capacity. (Klingberg et al., 2002) observed that children with ADHD too operate at a lower capacity and working memory training can significantly improve their performance. Similarly, working memory capacity is adversely affected by aging too (Salthouse, & Babcock, 1991).

2. Design Review

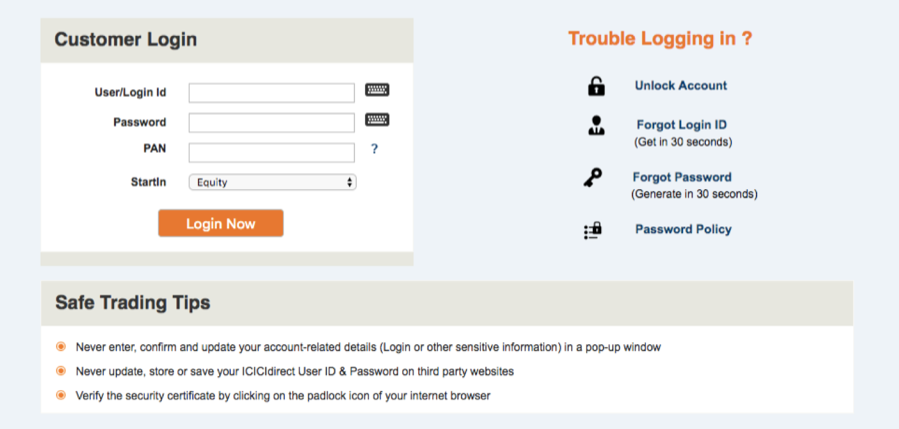

Figure 1: Log-in screen

User Id is defaulted to account number with no option to change (refer to figure 1). It is hard to retain a 10-digit account number in working memory, especially under conditions of high anxiety i.e., buying and selling of stocks at a particular price. A user might need to search for the account number while logging in. This extra task of searching for the account number, in this case, user Id, will lead to splitting of attentional resources resulting in errors while logging in. This extra task can also lead to increase anxiety levels of the users as there are high chances they will start worrying about missing the right stock price due to additional time spent on looking for the account number. Frequent users of the platform might keep the user Id/account number handy while logging in. However, while copying the user Id from this extra piece of information will also require additional attentional and working memory resources thus fewer resources will be available for the logging task and lead to degradation of performance. To make the situation worse, as shown in figure 1, login credentials also include PAN, SSN equivalent of India, which too is a 12-digit number. All the issues faced while entering the user Id will be repeated again while entering PAN.

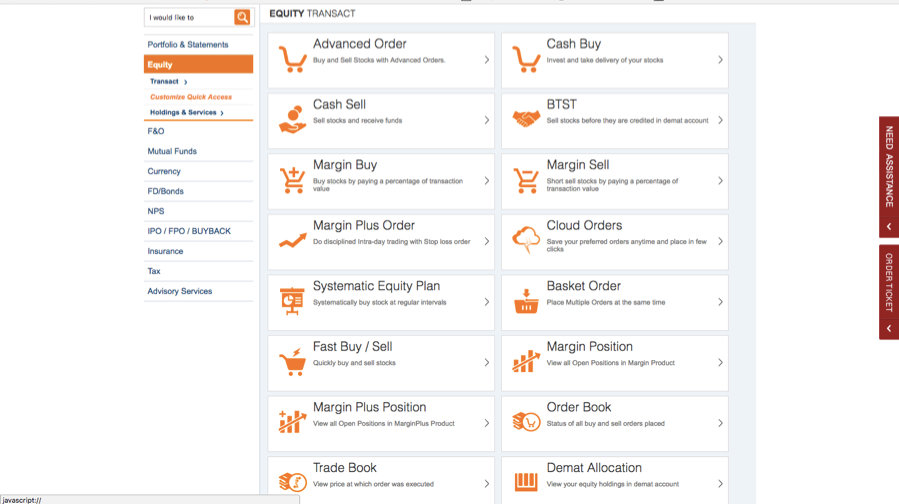

Figure 2: Equity screen

As shown in figure 2, 26 menu options are presented to the user inside the ‘equity’ section. Sixteen options are visible up-front, above the fold and the remaining options are revel upon scrolling. Such a high number of options will overload the working memory capacity leading to degradation of performance. Also, a lot of jargon is used for labeling the options. A large number of domain-specific options can overwhelm novice users and lead to arousal which too can result in degradation of performance.

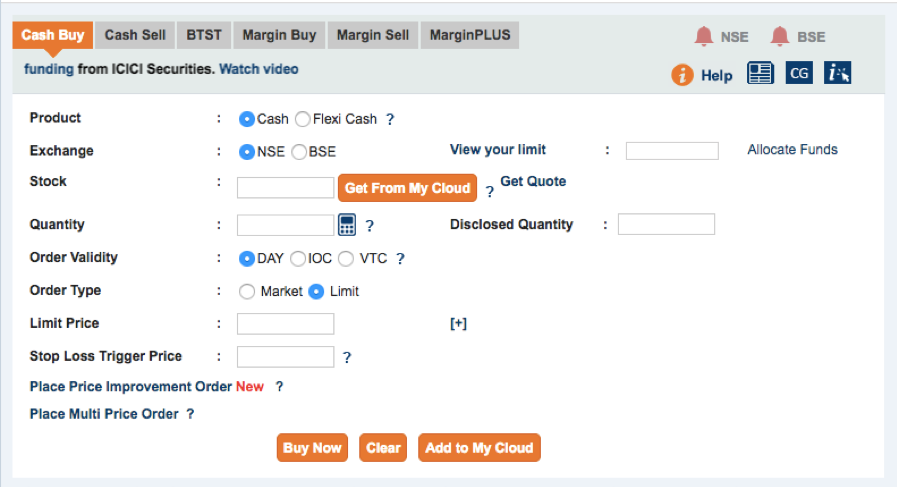

Figure 3: Investment screen

As shown in figure 3, while trying to buy or sell a stock(s), the user is asked to enter a lot of redundant information, which might be useful for expert users but will definitely overwhelm novice users, leading to arousal. To understand the overall experience of the system, a call was made to the call center seeking help. Even though the call center executive was very helpful, all the information required to proceed further was provided verbally. By the time the call ended, the current log-in session terminated and the system logged off automatically. In such situation, users will have to log-in, navigate to the investment screen, and enter all the data again. By the time users reach the investment screen, the support information, which was provided verbally by the call center executive, will decay as working memory has a limited duration. Also, the system requirement to enter account number and PAN while logging in will interfere with the support information retained in the working memory and may be forgotten.

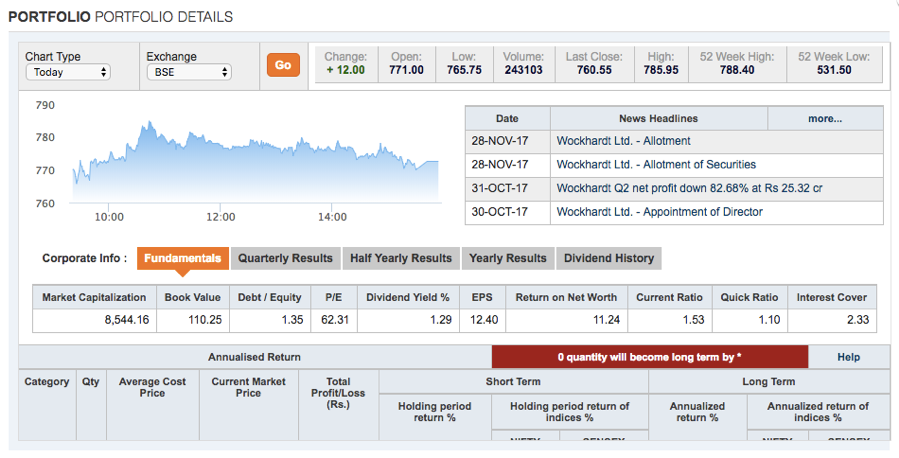

Figure 4: Stock details pop-up

When a user selects a stock form his portfolio, a pop-up appears displaying details of the stock’s performance as shown in figure 4. The details are presented in the form of interactive charts, tables, and text. This rich visual data is good for expert users as they will consume it in large chunks. However, for novice users dealing in lots of smaller chunks, such data representation might create cognitive load. The details in the pop-up seem to be scattered with no obvious grouping. It would be difficult for users to process such dense data pre-attentively, thus, making the users focus more on finding and comprehending data. This complex design exerts additional workload on the users which will affect their working memory capacity adversely. Also, the pop-up does not mention the name of the stock for which the details are displayed. The user needs to keep in mind which stock was selected on the previous screen. Due to the existing anxiety combined with the cognitive load and the additional workload exerted by the complex design, the stock selected in the previous screen will be forgotten. The user will, thus, have to close the pop-up and re-select the stock. The user might have to repeat this action while accessing details of each of the stock in his portfolio. This will add to the existing anxiety and frustration leading to further degradation of task performance.

3. Conclusion

This paper began with a brief description of working memory and described the limited capacity, short duration and highly volatile nature of working memory using existing research. The paper then focused on various factors like emotions, age, learning disorders, and attentional disorders that influence the working memory capacity. Further, the paper reviewed the current implementation of ICICIDirect’s investment management platform. The paper concluded that ICICIDirect’s design is very complex and may lead to the depletion of working memory capacity, leading to degradation in users’ performances.

References

Avery, R. E., Smillie, L. D., & de Fockert, J. W. (2013). The role of working memory in achievement goal pursuit. Acta psychologica, 144(2), 361-372.

Baddeley, A., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: advances in research and theory (Vol. 255, p. 305). Academic Press.

Baddeley, A. D., Thomson, N., & Buchanan, M. (1975). Word length and the structure of short-term memory. Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, 14(6), 575-589.

Baddeley, A. (2000). The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory?. Trends in cognitive sciences, 4(11), 417-423.

Brose, A., Schmiedek, F., Lövdén, M., & Lindenberger, U. (2012). Daily variability in working memory is coupled with negative affect: the role of attention and motivation. Emotion, 12(3), 605.

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336.

Goldstein, E. (2010). Cognitive psychology: Connecting mind, research and everyday experience. Nelson Education.

Henson, R. N. (1998). Short-term memory for serial order: The start-end model. Cognitive psychology, 36(2), 73-137.

Hu, Y., Hitch, G. J., Baddeley, A. D., Zhang, M., & Allen, R. J. (2014). Executive and perceptual attention play different roles in visual working memory: evidence from suffix and strategy effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 40(4), 1665.

Hu, Y., Allen, R. J., Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. J. (2016). Executive control of stimulus-driven and goal-directed attention in visual working memory. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 78(7), 2164-2175.

Klingberg, T., Forssberg, H., & Westerberg, H. (2002). Training of working memory in children with ADHD. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology, 24(6), 781-791.

Krawczyk, D. C., & D'esposito, M. (2013). Modulation of working memory function by motivation through loss‐aversion. Human brain mapping, 34(4), 762-774.

Luck, S. J., & Vogel, E. K. (1997). The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature, 390(6657), 279-281.

Lustig, C., May, C. P., & Hasher, L. (2001). Working memory span and the role of proactive interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(2), 199.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological review, 63(2), 81.

Peterson, L., & Peterson, M. J. (1959). Short-term retention of individual verbal items. Journal of experimental psychology, 58(3), 193.

Salthouse, T. A., & Babcock, R. L. (1991). Decomposing adult age differences in working memory. Developmental psychology, 27(5), 763.

Shackman, A. J., Sarinopoulos, I., Maxwell, J. S., Pizzagalli, D. A., Lavric, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2006). Anxiety selectively disrupts visuospatial working memory. Emotion, 6(1), 40.

Staal, M. A. (2004). Stress, cognition, and human performance: A literature review and conceptual framework.

Swanson, H. L. (1999). Reading comprehension and working memory in learning-disabled readers: Is the phonological loop more important than the executive system?. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 72(1), 1-31.

Taylor, J. A., & Spence, K. W. (1952). The relationship of anxiety level to performance in serial learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 44(2), 61.

Zhang, W., & Luck, S. J. (2009). Sudden death and gradual decay in visual working memory. Psychological science, 20(4), 423-428.